Howdy!

I was recently a guest on the Revision Wizards Podcast, where I had the pleasure of discussing my writing process, my approach to world building, and some behind-the-scenes insights into my creative journey. 🌍✍️

It’s about 40 minutes if you listen at a chill 1x speed.

I’d love to hear your feedback!

Check out the podcast >

In addition to the podcast, I recently received a wonderful foreword from none other than author/publisher J Thorn!

J Thorn is a versatile, best-selling author with over 20 years of experience in education and genres such as horror, thriller, and post-apocalyptic fiction. As a mentor to aspiring writers, he generously shares his expertise through blogs, workshops, and podcasts. He’s a major influencer in the indie-author community, and has been a staunch supporter of mine from the beginning.

From J. Thorn

One of the biggest challenges in writing an epic fantasy is the world building. This is no easy task for a seasoned author and practically impossible for a new author to master. But I can’t say I’m surprised.

I first met Don Elliott several years ago when he hired me to do a diagnostic on “A Nameless Town,” a short story about Roan before she went to Anubi.

Even then, I could tell Don had the “writer gene,” that undeniable yet undefinable trait that keeps readers turning pages. His imagery struck me as vivid yet specific:

“She roused them and soon they were criss-crossing dunes like the wrinkles of an old giant.”

That line from the manuscript stuck in my mind, and I kept returning to the visual throughout my day.

I met Monty before you did, and even though I didn’t know what a “petra” was, Don showed me what a petra did, and that was enough to hook me.

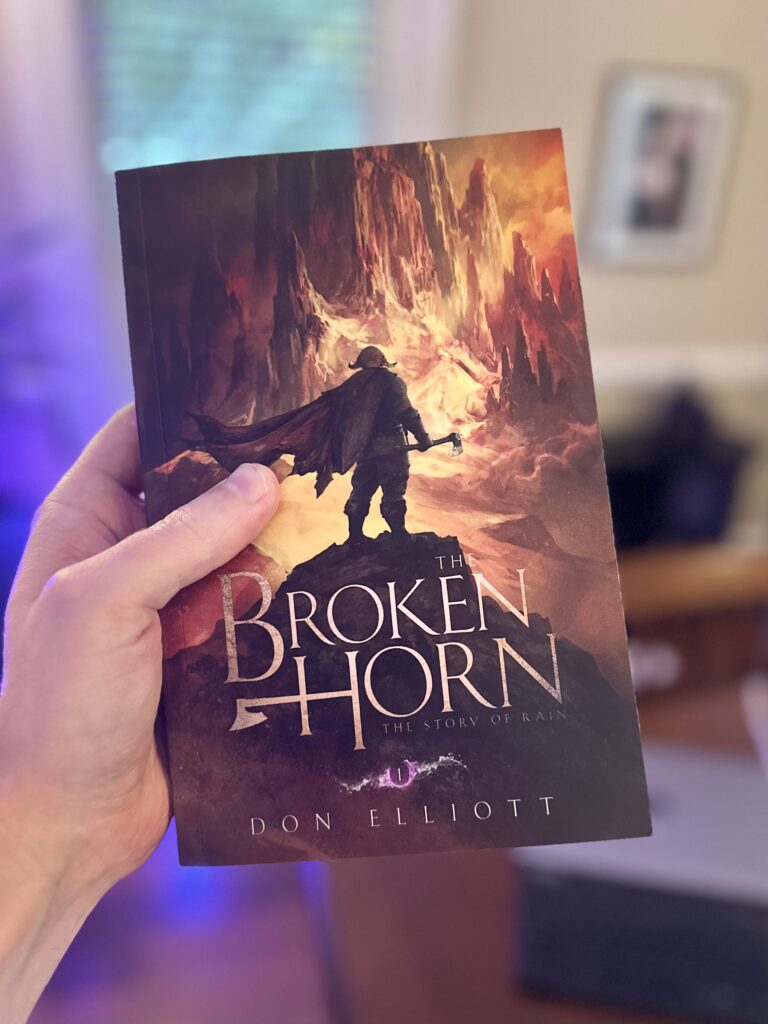

Fast forward several years, and I’ve just finished reading The Broken Horn. And now I want to become a sandrunner. In Elliott’s desert wasteland, I’m fascinated by Djeodi’s redemption arc and Roan’s reluctant hero’s journey.

I won’t spoil the story for you, but let’s just say you’ll love Monty even more by the time you get to the story’s climactic scene.

It always warms my heart to watch a person become an author, and I’m hard pressed to recall a debut novel as charming, captivating, and rich as The Broken Horn.

Ears here. Turn the page and start your adventure. Don’t dusting miss it!

I was pretty dang happy about that. Thanks J!

That’s all for now. It’s time I get back to working on book two. I’m officially 83% through with the developmental edit, which means I’m finally catching up on my timeline! It will be ready for BETA readers by the end of the month.

Have a great weekend!